The following are two reflections on a phenomenon that played a significant role in the world of the Templars and the accusations against them; this phenomenon was known by the name,

Baphomet

According to Bernard Marillier

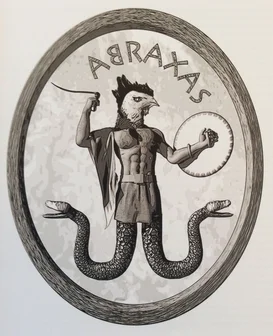

In the realm of Templar mysteries, the famous Baphomet is undoubtedly the figure that has most captivated the imagination of generations of authors, giving rise to a considerable number of insightful, surprising, or even completely mad hypotheses. First, let us note that the issue of Baphomet was central to the final accusation against the Temple, as the Templars were alleged to have engaged in a more or less ‘demonic’ cult, at least non-Christian, which would make them idolaters and lead them to certain death (cf. B. Marinier, BABA of the Templars). It should be noted that this term was never explicitly mentioned by the accusers or the Templars but only appeared in its adjectival forms, "baphometic" or "bafometic." The fact traces back to an Occitan brother from Montpezat, Gaucerant, who confessed to worshipping a ‘baphometic image,’ which, in the Occitan language, is a distortion of Mohammed, as shown in a 1265 poem, Ira et Dolor, E Bafomet, obra of his god: "And Mohammed lets his power shine." This brother was likely unaware that Islam forbids the worship of images and the representation of God, but this did not stop the accusers from seeing it as "proof" of the adoption of Muslim rituals by the Templars. Brother Gaucerant’s testimony was nonetheless the origin of a misunderstanding that allowed authors and occultists of later centuries to construct the term ‘Baphomet,’ giving rise to all manner of imaginable fantasies. From that point on, various etymologies were proposed: Baphe-metous, baptism of wisdom; Bios-phos-metis, life-light-wisdom; Bapho or Bafo, the name of a port in Cyprus which the Temple briefly owned; Abufihamat, a corruption of the Arabic phrase "the Father of Understanding," or from the Arabic Ouba el-Phoumet, "the mouth of the Father"; and so on. In testimonies, the Baphomet was often described as a head or a reliquary bust that the Templars were said to possess, which led to accusations of idolatry being levelled against them (report from April 1310): "They worshipped these idols or this idol. They venerated it as God [...], especially in their great chapters [...]. They said this head could save them. Make them rich. That it gave all its wealth to the Order. That it made the trees bloom. That it caused things to sprout [...]." The first testimony mentioning a head is from Brother Larchant (October 1307), who said he saw it in Paris, specifying that the brothers worshipped it, kissed it, and called it their Saviour. The appearance varied: sometimes male, young or old, with black curly or straight white hair, sometimes crowned, beardless, or bearded; at other times female, resembling a fairy or the Virgin; it could have two or three faces. Some witnesses said it was hideous and black like "the face of an infidel," a maufe (a devil or demon), according to Radulphe de Gisy, with shining eyes that caused great fear, but it was sometimes angelic and androgynous. Animal forms were not uncommon: heads of goats, rams, oxen, or black cats that could speak human language, give responses, and offer oracles. The material also varied: wood, sometimes gilded, bone, gold, silver, vermeil, covered with wrinkled human skin like an Egyptian mummy, or even a painting or a statue. Sometimes it was an actual human head. Almost all brothers admitted they had seen it very little, poorly, or only from a distance, as it was often displayed in a closed, dark place and sometimes covered with a veil. Many said they had only heard of an ‘idol’ but had never seen it. Disregarding the ‘demonic’ animal heads, specific to the demonological mindset of the Middle Ages, the ‘idol’ in question refers to a dual mythical-initiation reality of Indo-European and pagan origin. The first phase involved the "ritual of the severed head," a ritual based on all myths associated with the original tradition. It suffices to mention the head of the Gorgon Medusa severed by Perseus among the Greeks, the heads the Celts took from their dead enemies, which we find abundantly in the Grail cycle, the head of Bran buried in the White Hill of London, the prophetic head of Mimir among the Scandinavians, those of Goliath, Humbada, Curoi, etc. The ritual of decapitation is linked to a dual initiation: by severing the head of an enemy—the initiator, the victor—the neophyte conquered both the mana contained within the head and its spiritual power, leaving its fleshly shell to the ‘Spirit.’ Through the recitation of formulas and the enactment of dramatised scenes, the neophyte identified with the deity, enabling their spiritual rebirth in intimate communion with the divine. It was this type of ritual that the Templars, at least some of them, were subjected to, but in a ‘Christian’ sense and in line with the nature of the Order. Far from being an "idol," the Templar head, probably a false head or mask, or even a genuine reliquary, was the centre of an initiation ritual of a heroic-solar nature. Through the ritual of symbolic decapitation, the Templars, as both monks and warriors, conquered spirit and spiritual power, aligned themselves with the divine, and prepared to defeat both their visible and invisible enemies, those dwelling in the deepest realms of existence. The second phase involved the emergence of a timeless and dramatised universe at the extreme of consciousness specific to each Templar—which could explain the varied forms of the head described by witnesses—after the manifestation, in symbolic form and at a given moment of the rite, of a superhuman and transcendent ‘subtle figure,’ of a ‘daimon - demon,’ that is, of a genius linked to a higher reality than the neophyte had to experience and live through as a trial, a kind of ‘second baptism’ or dangerous catharsis leading to the conquest of gnosis, of the ‘Virgina Sophia’ which, according to the Templars’ own acknowledgment, provided eternity, glory, and riches, all of which must be understood at a strictly spiritual level (cf. B. Marillier, op. cit.). Therefore, it was through a true and complex esoteric-alchemical process that the Templar underwent—a process which, according to certain alchemical authors, notably Fulcanelli and Canseliet, could be affirmed in the fact that the name "Bapheus" can be translated as ‘dyer,’ which in the language of alchemists means: to bloom, to harvest, to reap the vital ‘sap’ of spiritual fire. To prove Templar idolatry, the accusers emphasised the powers of the ‘baphometic head,’ stating that it granted immortality, wealth, and health, and could cause the germination and blooming of plants (see above). Fulcanelli rightly observes: "The Baphomet is the synthetic image in which the initiates of the Temple had grouped all the elements of High Science and Tradition" (Les Demeures philosophales).

According to Marion Melville,

The most plausible explanation for the 'Idol of the Templars,' often described as a man's head on four legs, is that it was, in reality, a reliquary presented for the veneration of the brothers. However, it was still necessary to prove the existence of such objects. The portable reliquary of gilded bronze, made to preserve the relics of St. John the Evangelist, dating from the mid-12th century (depicted on the cover of the bulletin), closely matches the image one might have of Baphomet, with its haughty posture, the rictus of its mouth, its bulging eyes with heavy eyelids, although it is likely a portrait of Emperor Frederick Barbarossa. We do not claim that this reliquary ever belonged to the Temple, but we think it can be seen as typical of a certain style, a particular artistic formula, and that it was not the only one of its kind, reflecting a distinct taste for human physiognomies in the sculptural decoration of their chapels: the gigantic heads of Athlit, the grotesques of the Temple of London, the dead-end angel figures in Coulommiers, the elected officials and the rejected ones of La Ferté-Gaucher, to name but a few examples. We can assume that this tendency extended to objects of worship, which would explain the existence of a certain number of reliquaries in the shape of heads, sometimes with three faces: this would then symbolise the Trinity, as it exists in Orthodox churches. But why "Baphomet"? This mysterious name, which has given rise to so many false derivations, is nothing more than a distortion of the name of the Prophet, either in Provençal or in texts from the Latin Kingdom or langue d'oc, langue d'oil, and Italian, mingling into a lingua franca in which we commonly find bafomet and bafomeria for Mohammed and mahomerie (mosque). Two brother-sergeants of the Temple, interrogated in Carcassonne in November 1307, spoke of "a Baphometic figure" (in other words, a Mohammedan idol, which is nonsense; one of them added that this figure had the name Yalla (Allah). Logically, the denial of which the Templars were accused should have ended with a confession of the Islamic faith "raise the finger and proclaim the law," as Emperor Frederick II insinuated, to avenge his disappointment when he tried to seize Château Pèlerin by treachery and was caught in his own trap. "The Templars receive the Muslims as friends and participate in their rites, behind closed doors," he wrote to the kings of the West. But at the time of the trial, the memory of the siege of Acre and the sacrifice of the entire monastery of the Order was still too fresh for these accusations to be credible, even to the most gullible audience. Something else had to be found... "The idol" first appears as a simple stylistic figure in the text written by Nogaret in the name of Philippe le Bel, to order and explain the mass arrest of the Templars of France. "This filthy generation has forsaken the source of living water and replaces its glory with the (golden) Calf and offerings to idols." Is this not the memory of an illumination, "the hypocrites worshipping the Golden Calf," the first in a series of paintings made for La Somme du Roi, a manuscript calligraphed in Pontoise in 1295, undoubtedly for Philippe le Bel, who collected magnificent books and liked to display his library to those around him? Because Nogaret's text would come from the king's pen, it was a flattering reference to Philippe's erudition. In the instructions given to both the inquisitors and the king’s people on how the investigation should be conducted, the idol becomes a material object. "The Templars kiss and worship an idol that takes the form of a man's head with a large beard." But later it appears that the inquisitors (except in certain southern cities) barely pressed this idolatry, even when Hugues de Pairaud claimed 'that he had held this object during a general chapter in Montpellier, and that it was a man's head mounted on four legs, two at the front and two at the back.' (Like the reliquary portrait of Barbarossa.) By drawing up the list of one hundred and twenty-seven accusations presented to the Papal Commissioners in 1310, Nogaret made the idol the centre of a real cult. "The Templars have one in every province, in the shape of a man's head, with one or three faces, which they worship in their general chapters; they believe this idol causes wealth to grow, trees to bloom, crops to sprout, and livestock to become fertile." But here the ecclesiastical investigators no longer follow; it was dangerous to stir the ashes of certain pagan sects, and they limited their questions to the accusations first formulated: (denial, spitting, obscene gestures, sodomy, and the idol whose nature remains undetermined). As for the rest, the witnesses answered "that they know nothing" and the commissioners dropped everything Nogaret had added. The sacrilege of which the Templars were accused, therefore, remains meaningless; denial remains a purely negative act, and the idol a simulacrum. And this may seem all the more remarkable given that the Papal Commission gathered testimonies for or against the Temple considered as a collective entity, and not against the Templars individually. To conclude this overview with perhaps a frivolous question: 'the oath of children to swear secrecy': 'I make a cross and spit on it' the jokes of the children: "fuck my..." did they come after the trial against the Templars or before? To what extent did Nogaret joke about his people, pope, king, inquisitors, and victims, by launching the greatest and most cruel hoax?